Why Elections are Failing the Cute Cats

The person with the most votes shouldn't always win. The Cute Cat Appreciation Society is learning that lesson the hard way, and we should understand why.

A Song of Paws and Purrs

The Cute Cat Appreciation Society has a long and storied history, with former members including many of the most prominent celebrities, politicians, and zookeepers of past eras. At each meeting, the members adore cats both real and depicted with wholesome jubilation. If there ever comes an era of world peace, it will be ushered in by the sound of Society members coming together in the sound of a collective “awwwww.” But like any large group of people, they need a leader to help keep the meetings running, and so every June the Society runs an election for their President. And Society politics puts Game of Thrones to shame.

As election day approaches, the Cute Cat Political Machines are running at full speed. As with every election for this group, partisan fractures have turned friends into enemies as members find favorites and feelings run hot. A lot of candidates are running, and each candidate are extremists in their own ideological wing.

This year, Blue, Cyan, Purple, Green, and Red are running for President. Blue and Cyan have slightly different personalities but agree that we should work on appreciating a wider diversity of cats, especially those with missing limbs or those recovering from abuse. They are well-liked, but split their voters between them and make them both unlikely to win. Each accuses the other for failing to drop out, and the toxic infighting has revealed that both candidates seem to care more about power than policy.

Purple thinks the Society works great right now and promises stability, fairness, and a good work ethic. She would be an effective leader, but an unexciting campaign means she is nobody’s favorite. She is also a political newcomer, trapping her in the bottom ranks. Nobody takes her seriously, so nobody votes for her. And nobody votes for her because nobody takes her seriously.

The serious contenders are Red and Green. Red doesn’t believe wild cats are cute and wants to only allow housecats from now on, much to the horror of the scores of panther and lion enthusiasts. Green wants to have cats stop killing birds, mice, and other wildlife and ran on a campaign that killing isn’t cute. There are rumblings that Green is pro-declawing and maybe even anti-cat altogether, sparking widespread protests. Still, these extreme policy positions have their core and loyal supporters that put them in the top two, and many voters will vote for the one they hate the least to prevent the even worse candidate from winning.

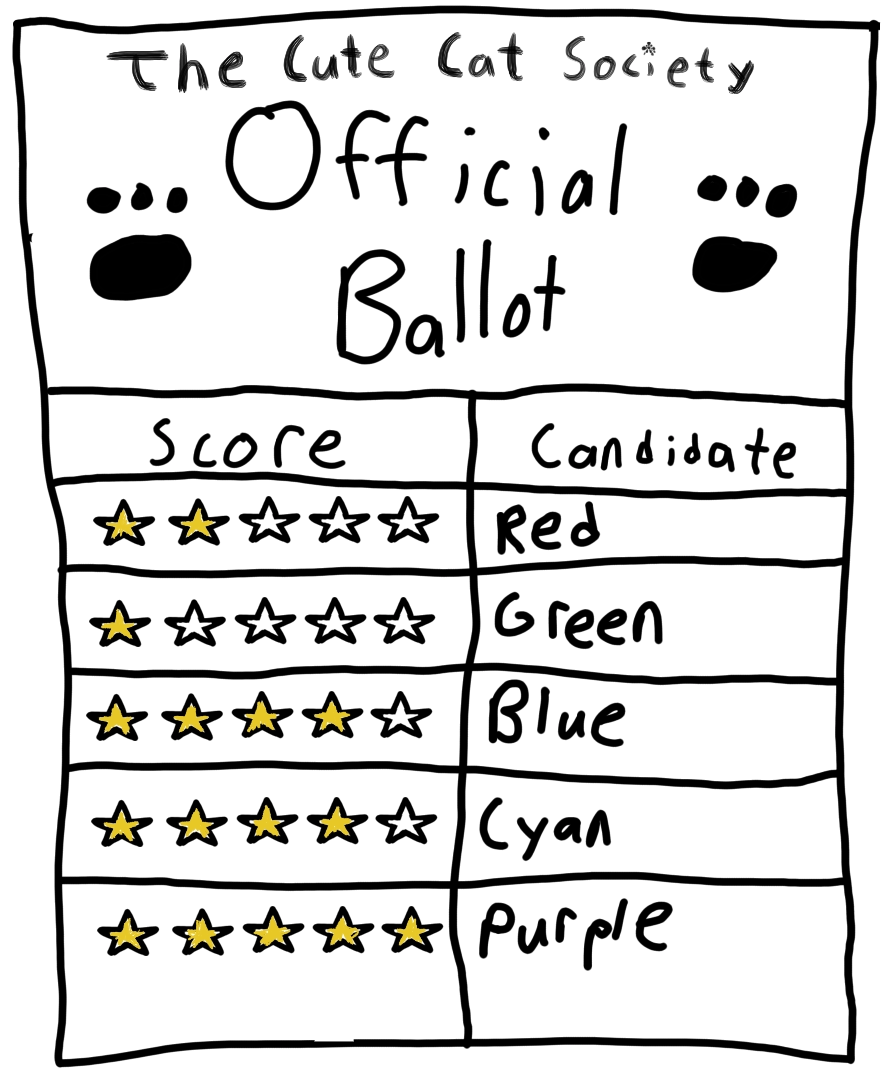

Here are the latest polls (yes, the Society has polls):

This election has awful prospects, and it is just the latest in a series of poor elections that have rocked the Society. The overwhelming majority of members are not happy that these dramatic elections keep happening and want it to stop. The Society has enlisted my help to make the elections better, and make sure the winner isn’t someone everybody hates this year. Let’s see what we can do.

Might or Right

If Green and Red are the only candidates who have a chance to win, why do so many voters want to cast a ballot for the others? The reason is that ballots have two conflicting purposes that cause conflicting behaviors: power and speech. Power means having the maximum impact on who wins the election by placing your vote where it is the most likely to make a difference: on Red or Green. Speech means expressing who you want to win the election most by voting for your favorite candidate. There are a bunch of votes for doomed candidates because many Society voters are putting speech over power.

In the Society’s current election system, known as Plurality Voting (also known as First-Past-The-Post or FPTP), everyone gets to vote for just one candidate and the person with the most votes wins. I didn’t need to explain this earlier because you probably assumed this was the default. While a simple and intuitive method, it also the one of the worst ways to balance the power-speech tradeoff. It offers very little means of expression – you can pick one candidate that you like and that’s it. And you often have to give up that little expression you have to get any power at all.

Democracy has been around for hundreds of years, yet elections have gone on nearly unchanged. You would think, in the age of science and reason, we would have figured out better ways to do things by now and make the process a little less terrible. In fact, we have. We began an earnest study of voting methods in the 1950s, and today that well-studied field is known as Social Choice Theory. Even before the theory was formalized, many countries had deep experience with alternative methods, such as Australia using ranked choice voting and many European countries using proportional representation for their legislatures. We can do better and we know how to do it.

Ideally, we’d have an election system where votes wouldn’t have to choose between speech and power. Unfortunately, this is mathematically impossible. Gibbard’s Theorem implies that every voting system has some situations where voters should vote strategically to get a preferred outcome. In other words, a voter must give up some of the expression of an honest vote to gain the power of a strategic vote. Not all hope is lost though – while we cannot solve this completely, there are many known solutions to lessen the size of the problem where strategic voting becomes less common and less useful. Let’s try to find one the Cute Cat Appreciation Society could use.

Meet the Competition

There are far too many alternative voting systems to list, but I wanted to give a taste of the options that are out there. An election system can be broken into two parts: how the ballots are designed and how to select a winner given the votes. If we use Plurality ballots where voters only choose one candidate, then electing the candidate with the most votes is the only sensible option. Thus to change our voting system we must use different kinds of ballots. There are two commonly accepted types: ranked ballots and rated ballots.[1]

Ranked ballots let voters express the order of their preferences by ranking the candidates.[2] So I could put Purple first, then Cyan second, followed by Blue, Red, and Green, like this:

There are three major voting systems that use ranked ballots. The simplest is Borda Voting, where we sum the ranks of a candidate on each ballot and elect the candidate with the lowest total. The next two simulate Plurality elections by assuming each voter would vote for the highest ranked candidate that is running. Instant Runoff Voting runs a series of Plurality elections where after each election the candidate in last place drops out, repeating the process until someone gets a majority.[3] Condorcet methods elect the candidate who earns a majority when in a one-on-one election against their strongest competitor,[4] with various tiebreaker rules if no one can do this.

Rated ballots, by contrast, let voters express the strength of their preferences by placing the candidates on a scale. Potential scales include 0-5 stars, points between 0 and 100, or even the grades A-F. For example, if we are using a 0-5 star scale I might give Purple 5 stars, Cyan and Blue 4 stars, Red 2 stars, and Green 1 star like this:

Rated ballots can be converted into ranked ballots (by giving the highest rated candidate 1st, the next highest 2nd, and so on), while the reverse is not true, meaning rated ballots are more expressive.[5] This is a double-edged sword: more expression often comes at the cost of more room for strategic voting.

The most common rated method is Score Voting, where voters rate on a numerical scale and the candidate with the highest average score wins. Judgment Voting uses a qualitative scale with ratings like “good”, “okay”, and “poor” and elects the candidate with the best median grade (along with some tiebreaker method).[6] Approval Voting is identical to Plurality except voters may vote for as many candidates as they’d like. It is technically both a kind of Score Voting (scoring on a 0-1 scale) and Judgment Voting (judging either as “approve” or “disapprove”) since these all have the same results, which gives Approval Voting some properties from both systems.

It is impossible to say which one of these systems is best. All of these systems have their uses, and different systems will be more favorable to different cultures and situations. I tried to write a post comparing all the major options, but it turns out I had a lot to say. Too much, in fact, to contain in a single post.

Instead, I will be writing a series of posts on voting and the different ways we can make it better. Each post will be split into two sections, one defending the voting system and the other pointing out its flaws (and trust me, every system has its flaws). Each system has its uses, and whether it will be the right one for the job is ultimately up to you.

There is no point to change if we don’t understand that there’s a problem, so in this first post I will try to justify the entire series by talking about Plurality Voting. I’m going to try to show that there are serious problems with Plurality Voting that warrant looking for alternatives. But I am also going to point out its strengths, and show that sometimes it may indeed be the best way to run an election.

So let’s get started. The cute cats are counting on us.

The Benefits

I think that Plurality Voting is probably the worst way to run a high stakes election. But there are good reasons we’ve stuck with it for several hundred years. We would be foolish to discard the system too hastily, especially without understanding the benefits of using it that we may have taken for granted. So here are the best reasons why we shouldn’t change the way we vote.

The Story

Every society has a story that justifies why the people in charge get to lead. Kings tell the story of a mandate from Heaven, where God (or some divine force) placed them on the throne to carry out their will. Other stories are less dramatic: Susan is in charge of her school’s Chess Club because she is the one organizing the meetings, Mark Zuckerberg leads Meta because he founded the company, a parent leads their child because they are older and wiser. These stories are often enforced by law or custom, but that law only exists because of the story that justifies it. Without a compelling story, no one would follow their leaders and there would be no power.

Democracy, in some sense, is just another story: the person who is in charge is chosen by the people and leads with the consent of the governed. Elections are in some sense an act of theater, a great show for the people that tells this story every few years. Those who believe this story will accept their leaders as legitimate, even if they do not like them and did not vote for them. Democracy persists only as long as people continue to believe this story.

Different voting systems will tell different versions of this story, some simple and others complex. Plurality tells the simplest story of them all: the largest amount of people wanted this person to lead, and so they shall. This is easy enough for even a small child to understand and easy for people to believe, and that ensures that the foundations of democracy remain strong.

Other voting systems might select more “optimal” winners by various metrics, but selecting an optimal winner is secondary. The primary aim of a voting system is to select a leader that has a mandate from the people and that people will accept as legitimate. Nobody can doubt the person with the most votes has a strong mandate, and the simple story makes them the easiest winner to accept. Other systems will lead to people casting doubts. In a high stakes election where the foundations of democracy are often put to the test, it is the simplest solution that shines the brightest. Any other system imperils the democratic enterprise.

Running the Election

Elections are hard to run. While a club president can often be selected by a mere show of hands, large elections quickly get complicated. There must be systems to ensure voters are valid and only vote once. Ballots must be stored securely and have a robust chain of custody. And large quantities of ballots need to be counted quickly to get results. All of this needs to be done in a transparent manner so all sides can agree that the results are correct. Plus there are often other requirements, such as access to ballots in different languages and provisional ballots that are only investigated if the election is close enough that they may determine the outcome. This is hard enough, so it would be unwise to make this process more difficult.

There are many benefits to Plurality Voting that make it the easiest possible voting system to run an election with. It is simple to count, involving only counting the number of ballots in favor of each candidate. The process is easy for an observer to verify is being done correctly. Precincts can count independently, so ballots do not need to be centralized before counting begins. In case of a recount, it is easy enough to verify computer counts by hand or recalculate results if a ballot is rejected. As a consequence of these factors, elections outcomes can be determined quickly and with confidence.

We take all of these facts for granted, but with a different voting system many of these factors are no longer true. Any other voting system will make running an election more difficult, with slower results and more chances for error.

Easy to Understand

What do you think of when you picture a voter? You might imagine a partisan activist, attending a few political rallies and defending their ideology in toxic Facebook comments. Or you may think of a diligent moderate, passively consuming political news and watching the candidates debate on TV before deciding. Or perhaps even the disillusioned independent that casts a blank ballot to express their hatred of the system and the choices they’ve been given. These voters will probably understand or figure out how the voting system works, even if the one being used is a bit complicated.

But when we think of voters, we also need to think of your great-grandma, whose eyesight is failing and needs to be told something multiple times for it to stick. Or your office janitor who speaks only broken English and can’t understand the news. Even your 18-year-old stoner nephew about to graduate high school with barely passing grades. All these people vote too, and all of them need to understand the voting system.

Changing the voting system and explaining it to voters is no easy task. There is a reason changes in voting systems come with multimillion-dollar voter information campaigns to try to help people figure it out. Even now, ballots are often designed in confusing ways and can trip up many voters. The extra complexities of ranking or rating candidates will only add to the confusion and disenfranchise voters like these.

It is possible to overcome this. Evidence shows that voters can figure complex systems out if you put in the effort to make the election accessible. But this is no easy hurdle, and it makes switching to any other system more difficult than merely modifying the ballots.

Easy to Decide

I tend to be pretty confident in my first choice during elections. Not so much for my second or third. I suspect this is partially human nature: our favorites are deeply held convictions, while later preferences are less so. Plurality asks only for the voter’s favorite and thus their most deeply held conviction, allowing us to decide the winner on a strong foundation.

Other voting systems will ask for more, either your rankings or your ratings, which will entail evaluating second, third, and even later choices. These are more difficult questions, and as a result I think voters will be less confident in their answers. Relying on these secondary decisions to pick a winner creates an illusion of consent by basing the decision on voter’s whims and uninformed decisions rather than their confident and reasoned convictions.

Widespread Use

We ought to stick to the status quo. Plurality Voting is being used in elections all over the world and is working fine. We do not need to take the risk with other systems.[7]

This is a bit of a cynical take. After all, innovation needs to happen, and that means making risky decisions that sometimes don’t pay off. This is certainly true in science and engineering where innovation drives progress, but that’s less true for voting. When deciding on the mechanics of our democracy, low risk is far more important than innovation. After all, democracy has been working for centuries, so it clearly isn’t that broken. If a candidate people don’t like wins the election due to an innovative voting system, they’ll blame the system. But with good ol’ Plurality Voting, most people will blame the voters instead.

Perhaps we should innovate in democracy in some places, especially those that are lower stakes, to see if we can make something else work. But until something else becomes widespread, the risk isn’t worth it.

Less Division

Plurality Voting tends to result in races with fewer candidates (I will explain why in my opposition). Sometimes this results in no good options, leaving voters feeling like they are picking the lesser of two evils, and that sucks. But there is something to be said in favor of having limited competition.

We should take care to ensure there are not too many political parties. Too many parties makes it very difficult to build consensus or negotiate deals between them for the same reason it is easier for a pair of friends to decide where to go out to dinner than for a group of ten friends to decide. Especially in legislative elections where parties need to agree with each other, excessive fractionalization quickly leads to deadlock.

Furthermore, too many choices makes voters’ lives more difficult. Properly vetting one or two candidates to make sure they have good ideas is already difficult and time-consuming; properly vetting five or six candidates is overwhelming. Debates will be less focused and consequently less informative. Unbiased news coverage giving credence to five different political philosophies is hard to do even with the best of intentions, so news quality will likely degrade. It will be easier to miss candidate red flags. Less informed and less confident voters will lead to worse voting and more bad choices.

By reducing the number of viable options, factions are forced to coalesce into ideologically broad camps that either give them a majority outright or make dealmaking between them tractable. Voters need to be familiar with fewer candidates to cast an informed vote, making their lives easier. And since candidates have to represent such large portions of the electorate when there are only two or three parties, the winner will be satisfactory to a large swath of people instead of narrowly supported by a small minority faction.

In cases where there are multiple candidates and there is a risk of vote-splitting, there are tried and true methods to help alleviate this issue: primaries and runoffs. The first election lets the most popular candidates in a broad field advance, and the second lets voters learn about the candidates in depth and make an informed choice. In the end, majority rule will decide the winner.

The Opposition

Simplicity is a virtue, and Plurality has it in spades. But that is not all there is to voting. People have a right to be represented in government and be part of the debate, and voting systems that undermine that ability are troublesome. A voting system needs to pick a winner that fairly represents the people, and it needs to choose winners that will benefit society. Plurality Voting fails these criteria dramatically, in a way that simplicity alone cannot redeem. Time to look at how this system goes wrong.

Spoiled Chicken

I want to look into the story about Blue and Cyan. Let’s look back on those polling results:

Red is set to win here. But if Cyan wasn’t running, their supporters would have voted for Blue instead. In that case, the election would have turned out like this:

Now Blue is winning!

Cyan is a spoiler, a candidate who cannot win but can change who wins by taking away votes from others like Blue. Neither Blue nor Cyan want this, and neither do their voters. My defense suggested using runoffs to deal with this, and that sometimes works. But a top two runoff doesn’t solve the problem – in this case, Blue would still lose because they were only 3rd place. Besides, having a runoff doubles the cost of the election and often has a reduced turnout. To deal with spoilers, we need to do better.

Ideally, Blue and Cyan would join together and form the Aqua political party. They would both run in the party primary and agree that whoever loses will drop out and support the winner in the general election. This would prevent them from splitting votes in the main election while still giving both of them a chance to win. Even if the loser didn’t drop out, many of their supporters will switch to prevent a split vote.

Candidates who are splitting votes can’t be forced to join a political party though. Furthermore, we haven’t solved the problem, because if more than two candidates run in the same party primary then they could spoil each other in the primary and we’re back to square one. In fact, spoilers and vote-splitting is even more problematic in primaries because all the candidates are ideologically similar. If anything, this makes it more important to come up with a better voting system for primary elections than for general elections.

The Society doesn’t have political parties and won’t organize party primaries. So the only way for Blue or Cyan to win is for the other to drop out. Blue would prefer Cyan winning over Red and can guarantee that outcome by dropping out. But Blue prefers to win, and figures Cyan should be the one to drop out instead. Cyan uses similar logic and also doesn’t drop out, figuring Blue should be the one to do so if they really cared about beating Red. Thus, Red wins despite that being the least preferred outcome of both Blue and Cyan.

This is known as the Chicken dilemma, named after the game of Chicken. Blue and Cyan are engaged in such a game – each needs the other to “chicken out” and leave the race, letting the other candidate win. But if both candidates try to win, they both lose. We have to change voting systems to avoid this problem.[8] Otherwise, infighting candidates can throw away a winning advantage, spoiling the race and undermining the will of their voters.

My defense discussed how only the most deeply held convictions of the voters should be used to decide the outcome, but now we see the problem with that logic. Without taking into account the later preferences of voters, Red was set to win with only a third of the vote despite Blue being more popular. Voters may not always have strong second and third preferences, but when they do taking them into account will find a winner that better reflects the will of the voters.

Betrayal and Regret

Plurality Voting is the worst election method in terms of expression, since the ballots give the voters little opportunity to express themselves. But since an election’s primary aim is to elect, perhaps this isn’t important. But what about power? When we look at how Plurality Voting empowers voters, the problems look even worse.

I’m going to use the last example for polling data again:

Purple is clearly a doomed candidate here. The real election is between Red, Blue, and Green. Tactical voters regret voting for Purple, because they feel like they don’t actually get a say in who between these three candidates wins the election. So some Purple voters abandon her for the other candidates, leading to this:

Well now Purple looks even more doomed than before! Some Purple voters were holding on for the symbolism of their vote, but now even that seems wasteful. This is common – the worse a candidate does, the less willing voters are to support them. This vicious spiral means that candidates that start to do bad quickly lose all their support:

Purple’s votes are now a rounding error, and she drops out of the race shortly thereafter.

Green’s voters should be subject to the same pressure that Purple’s were. After all, their candidate is losing by a 12% margin, which cannot be practically made up. Some Green voters, for instance, hate Blue and vote Red to stop them from winning, and likewise for those who hate Red and prefer Blue:

But many Green voters dislike Red and Blue and don’t care who wins between them, so they’d rather stick behind their candidate than help one of the other candidates win. This is another common feature of Plurality Voting – candidate support outside of the top two is suppressed. Even though Green is the favorite of 27% of voters, they receive only 20% of the vote.

Finally, a new candidate Yellow enters the race last minute. A bunch of voters say they really like Yellow, but when the poll is conducted the results look like this:

Despite a bunch of voters liking Yellow, few are willing to change their votes because they don’t think Yellow can win. But voters won’t think Yellow can win unless they get a lot of votes, and so we are stuck with a bootstrapping problem. This makes it very hard for new candidates or parties to appear.

All these examples are demonstrations of the same behavior: voters choosing who to vote for based not only on who they like the most, but also who has the best chance of winning. From the voter’s perspective, they are making a strategic call between voting for their favorite to help them win, or voting for a less-preferred but popular candidate to stop an even worse one from winning. This leads to many voters betraying their favorite candidates, which is not a sign of a good system.

Furthermore, even voters who have no qualms with betrayal will find themselves in trouble. In these examples, the voters were fortunate enough to have highly accurate and regular polling – a fact that is not generally true. Most of the time, voters will learn whether their vote was put to good use when they see the election results. In this uncertain environment, some voters will inevitably get the strategic call wrong by voting for unpopular candidates, effectively throwing their vote away. These voters regret their vote and wish they could change it. All voting systems will have some scenarios with regretful voters but Plurality has this almost constantly. And voters constantly regretting their vote does not inspire confidence in the winner.

The Force

Voter strategy causes candidates to leave the race just like Purple. It also makes it hard for new candidates or parties to enter the race, like with Yellow. As an implication of these factors, the number of candidates should drop over time. Voters are only ensured to have no regret if they voted for a contender in the top two, so whenever there are more than two candidates these factors are pushing for one of the candidates to drop out. Taken to the logical extreme, eventually only two contenders will be viable and the result is a two party system.

This process is called Duverger’s Law, though it isn’t a law (nor did Duverger call it a law) and it is generally exaggerated. Americans have historically latched onto this “law” to explain the long two-party dominance in the country, ignoring other countries with the same system and more parties like the UK and India. American two-party dominance cannot be fully explained by the voting system, and a new voting system won’t necessarily fix this problem.

Rather than a law, these tactical pressures that Duverger identified are better thought of as a force, pushing candidates to drop out and voters to consolidate until there are only two viable contenders. This Duverger force can be resisted by countervailing forces like ideological diversity and expressive voters. We saw how the Society elections didn’t reduce all the way to a two-party system, despite the Duverger force pushing Green voters to vote for Red or Blue, because many Green voters felt unrepresented by the other two candidates. Due to the Duverger force there tend to be very few candidates running in Plurality Voting systems, though not necessarily just two.

In my defense of Plurality Voting, I talked about how reducing the number of parties can be good since it prevents excessive fractionalization and simplifies the voter’s decision. At some level, this is true. But the reverse is also an issue: we need enough parties to represent all the voters.

The Duverger force is often too strong, suppressing the competition below its natural limits and causing many voters to end up feeling unrepresented in the candidate pool and bitter about politics. Often, two or so factions are not enough to represent the large diversity of opinions of the public. Even if they don’t win, viable candidates from other factions can shape the debate and force favorable promises and compromises out of the eventual winner on the campaign trail. Voting systems like Plurality suppress this, leaving many voters voiceless.

Too little fractionalization can also cause deadlock. In a two party system, it is easy for both parties to end up with veto power and cause standoffs, with no one willing to back down. With more parties at the negotiating table, no one has veto power because the others can team up against them, and this forces everyone to negotiate in good faith and get stuff done. More groups might make negotiation harder to manage, but it will ultimately result in better outcomes.

Controversy

Everyone thinks Purple is alright, so why does Purple poll so poorly? Plurality Voting elects the candidate who the most voters think is their favorite. Second place in a voter’s heart is as good as last, so it is better to be the favorite to a few and hated by the rest than decently liked by everyone. Compromise candidates support policies that most people would get behind, but tend have trouble getting favorite status against the controversial candidates that voters perceive as fighting for their tribe. In essence, it is better to pick a side than heal the division.

Negative Campaigning

In Plurality Voting, a candidate convincing an undecided voter that they are the second best has not earned a vote and thus wasted their time. This limits the effectiveness of positive campaigning. On the other hand, convincing the same voter that a top competitor is bad and taking away a vote is time well spent. Negative campaigning is thus a far better strategy in Plurality elections. With fewer candidates due to the Duverger force, fewer candidates need to be targeted for negativity, and that makes the strategy even more effective.

Story

I started my Plurality defense by arguing it told the best story, so now that we understand the system we should evaluate if this claim is true.

A simple ballot tells a story too. On a Plurality ballot, there is no room for second best, nor compromise, nor nuance of opinion. The person with the most votes is not the most liked, but the person with the most uncompromising support. The winner is the bully that scares away similar candidates, supports radical policies, won’t listen to anyone who disagrees, and spouts negativity about everybody else. Plurality Voting is the story where the bullies win.

Democracy isn’t supposed to help the bullies. It’s there to stand up for the little guy, the less powerful people who don’t have the money or the platform to influence the world. People like your grandma, your janitor, and your stoner nephew. They don’t have fame or fortune, but they do have a vote, and so come every election the powerful people need to listen to them for a change. We should make that count for something more, and ensure the bullies don’t win.

We have better stories we can tell. A story where the winner won by genuine support and not strategic finesse. Stories where the most liked candidate leads, or the one with majority support, or the one most people can agree on. Stories where the winner is the best person we could find. Plurality tells none of these stories.

In my defense I said the Plurality winner would be the easiest to accept because of the system’s simplicity. But now I ask: do you think it would be easier to accept the simplest winner, or the best one?

Now What

Plurality Voting is a simple and well-understood method that has stood the test of time. Its key benefit is making everything easy: easy on voters, easy on election administrators, easy on the media reporting the results. This ease means we shouldn’t abandon Plurality without good reason.

However, we have plenty of reasons. It is a system that encourages controversy and negativity, that suppresses competition, that punishes compromise, and that limits expression. While Plurality is easier, the alternatives are better: better for voters who have more choices, better for candidates less worried about spoilers, better for government no longer ruled only by extremists. This might make elections harder to run, but I hope I can convince you in the coming posts that this is worth the cost.

My mandate from the Cute Cat Appreciation Society was to make their elections less toxic and elect candidates that are well liked. Plurality is inevitably at odds with this goal. For the sake of the cats, let’s try to find something better.

The next post in this series will be on Score Voting. Subscribe to the newsletter or RSS feed if you don’t want to miss it.

Footnotes

I am calling these ballot types ranked and rated, but another common split I’ve seen in many discussions is ordinal and cardinal. These categories are similar but not the same. Ranked and rated are more general and encompass more systems, and are also easier words to understand. These are the same categories used by ElectoWiki. ↩︎

Generally, you don’t need to rank all the candidates. In fact, many ranked ballots also only allow ranking a few candidates (typically your top 3), which can cause problems when there is a large field. Rarely, ballots will let you give two candidates the same ranking if you are indifferent between them, which can be handled in a variety of ways depending on the method used. ↩︎

In the US this IRV is called “Ranked-Choice Voting” despite not being the only way to vote with ranked choices. In the UK it is called the Alternative Vote despite not being the only alternative voting method. I refuse to call it either of these things. ↩︎

Note that only one candidate can achieve this. The winner earns a majority against their strongest competitor, so they would by definition have a majority against every other candidate. Since every other candidate earns only a minority of the vote against the winner, they cannot do better against their strongest competitor. ↩︎

Eagle-eyed readers might notice that the example I gave cannot be converted into a ranked ballot. This is because Blue and Cyan were close enough for me that I rated them both 4 stars even though I slightly prefer Cyan to Blue. This can happen generally when there aren’t enough ratings to distinguish similar candidates. ↩︎

“Judgment Voting” is a term I made up. Majority Judgment was the first prominent version of this system, advocated strongly by some French mathematicians, which has a set list of grades and a specific tiebreaker system. When another scientist generalized the system and devised a few other tie-breaking methods, they called their modified systems names like “Usual Judgment” and “Typical Judgment”, so “Judgment Voting” felt like a consistent name for this family of systems. It’s also less of a mouthful than Wikipedia’s “Highest median voting rules.” ↩︎

There’s a classic phrase in the tech industry that says the same thing: “nobody gets fired for buying IBM.” ↩︎

Specifically, to avoid the Chicken dilemma we need a voting system that satisfies the Mutual Majority Criterion, ensuring that if a majority supports a group of candidates, one of the candidates in the group must win. ↩︎